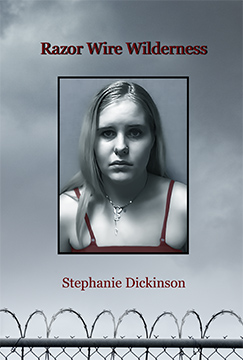

RAZOR WIRE WILDERNESS by Stephanie Dickinson

Reviewed by Andrew Kaufman

|

Norman Mailer's Executioner's Song and Truman Capote's In Cold Blood would be considered two of the greatest American novels of the second half of the 20th century if these "nonfiction novels" were technically novels. Both tell the true stories of gruesome, senseless murders committed against strangers whose only mistake was being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Both make copious use of extensive, repeated interviews not only with the killers, but with everyone willing to be interviewed who had ever known them or their victims. Both also mine the paper trails created by police investigations and those left by the legal proceedings that resulted in the convictions and sentences. Both books center on murders that had received extensive sensational publicity at the time, both devote significant attention to the difficult childhoods of the perpetrators, who in both instances had an extensive criminal history, and both eschew the trappings of the murder-mystery genre. These two books far exceed the scope of the murders themselves to reveal a great deal about the cross-sections of American society that the murderers come from and that the murders touch or intersect with. Both of these books transcend being merely reportorial in their use of techniques characteristic of fiction, such as the free-associative movement back and forth in time, the evocative use of imagery, and the intermittent the stream of consciousness of central figures, made possible by extensive, repeated, in-depth interviews. The above descriptions all apply equally to Stephanie Dickinson's Razor Wire Wilderness, a worthy addition to the genre that earns a place in this company. At its center is the rape and murder of Jennifer Moore, a college-bound eighteen-year old who had graduated high school two months earlier, who after a night of heavy underage drinking with a friend at a club in New York City found herself wandering alone on a desolate stretch of road. She was kidnapped and murdered by Draymond, Coleman, then a drug-addled thirty-four-year-old pimp and small-time drug dealer with an extensive arrest record that included a five-year prison term, who police say raped, savagely beat Jennifer Moore, fracturing every bone in her face, strangled her, and then had sex with her corpse. He was the pimp for Krystal Riordan, his live-in girlfriend, a twenty-year-old street-level prostitute at the time who received a thirty-year sentence for her contributing role in kidnapping the victim, tampering with evidence which included her role in disposing of her body. Much of the book is devoted to Krystal, detailing her difficult childhood and her time in prison, along with the murder and the events that led up to and immediately followed it. Razor Wire Wilderness presents Krystal's conduct surrounding the murder in excruciating if not unbearable detail, from her role in luring the victim into the seedy SRO hotel room where Krystal was living with Draymond Coleman, to the description of her impassively wandering in and out of the room as Jennifer Moore fought for her life, getting potato chips from a vending machine and drowning out the sounds of the struggle by blasting the television. Nonetheless, as seen in a number of responses to this book on Amazon, some readers are put off by the amounts of sympathetic attention and professed friendship Dickinson shares with her, especially in the apparent absence of contrition beyond the pro forma apology offered at her sentencing hearing. It's arguable that the large black-bordered picture of Krystal that dominates the front cover wasn't the most representative or tactful cover option. The relationship between writers and imprisoned killers has at times been notoriously fraught. Truman Capote obtained many of the details that distinguish In Cold Blood after becoming romantically involved in the course of prison interviews with one of the two killers the book focuses on. Having promised Perry Smith to show his "human side" to the world, Capote abandoned him entirely once he had the details and insights he needed from him, leaving Smith's pleas for contact of any sort unanswered in the lead-up to his execution. At the opposite end of this spectrum, due in significant part to a public lobbying campaign by Norman Mailer, Jack Henry Abbott was released early from prison despite a manslaughter conviction, only to stab a waiter to death six weeks later following an argument about the use of a bathroom. It would be a mistake for readers or prospective readers of Razor Wire Wilderness to allow themselves to be waylaid by the friendship accorded Krystal Riordan and at least one of her fellow inmates who became Krystal's friend at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility, the lone prison for women in New Jersey, which lends this book its title. The state's governor recently ordered that this prison be closed due to the facility's long and sordid history of abuses. Dickinson points out the proximity in age between Jennifer Moore and Krystal Riordan and observes that this can be an especially risky and vulnerable time, particularly for women and especially for those who had grown up in restrictive or sheltered environments, whose curiosities about the outside world exceed their abilities to assess its lurking dangers. She describes her own experience, not long after completing high school, of hitch-hiking partly across the country to meet her boyfriend at the time, a visit that left her permanently disabled after she was shot at a house party by a jealous suitor. The parallels drawn to the misjudgments that left Jennifer Moore in harm’s way may be broadly applicable, but any drawn to the choices Krystal made are far less so. Yet either way, based not only on interviews but also on the author's eight-years of correspondence with Krystal Riordan, this book contains some of the best-written, most viscerally compelling prose that has been produced in this country in the current century. Its accounts of the lure of heroin are among the most seductive I've seen in recent writing. Its depiction of the dehumanized hell that accompanies full-on addiction are at least as harrowing as readers are likely to come upon. Both call to mind Thomas De Quincey's astonishing early 19th century classic, Confessions of an English Opium Eater. Krystal's decade and a half in a maximum security unit for women is evoked with an equally visceral, disturbing understated immediacy: By 7:30 a.m. Krystal is heading down the moldy hall. Because of all the buckets set out to collect water leaking from the ceiling, she figures it rained last night. Even the air hates being here, air breathed in and out of so many bodies it’s turned into silt and soil to be tamped down with stones and electric wire. The air carries stagnant time; it clings to the nostrils. Seldom has an author made such visceral uses of smell, as Dickinson does here and in her evocation of Krystal's work as a street-level prostitute, carried out in the SRO she shared with Draymond Coleman and in any number of similar rooms: Sex work smells of the window left open, no, the window broken; it smells of all-nighters, a hot room where it snows in the closets, the money neon-green as the slop water at the bottom of a boat. As deeply familiar as the book leaves us with what had come to pass as day-to-day quotidian prison reality for Krystal Riordan, the following account is shocking to an extent that it stays with and haunts us, as much through the author's understatement and control as in its content. The passage describes Krystal's resumption of her sex work in the same room, on the same bed, and, later, on the same day as the rape and murder of Jennifer Moore. Dickinson frames this passage by making clear that it occurred just hours after Krystal had helped her boyfriend and pimp remove DNA from the victim's fingernails and elsewhere, stuff her body into a duffel bag, dispose of it in dumpster, and then flip the mattress so the blood stains would be less evident: The day's sounds gather force, a purple river of trucks backfiring and fire engines honking. She offers him the $150 special, his choice of two, but he only wants oral. When he unzips she cuddles his sex and licks and blows him especially nicely. His crinkly hairs have an oregano scent mixed with nutmeg, as if he has washed himself not long before. That kindness makes her eyes tear. She brings him to his climax easily. There are two more men. The younger white guy wants the special: anal, oral, vagina. His crotch tastes moldy, maybe of Gouda cheese. In the future stretches her 30-year prison sentence. It's tempting to conclude by saying that anyone should read this book who has ever wondered how our shared humanity, in some cases at least, can accommodate itself to acts and circumstances that are unthinkable. But this doesn't do justice to Razor Wire Wilderness. Stephanie Dickinson has presented us with a revelatory picture of actions, temptations, degradations and horrors that are made to feel as real as our own daily lives, but which achieve archetypal stature in their vividness and power. This is book is a visionary achievement. —Andrew Kaufman Andrew Kaufman grew up near NYC, graduated from Oberlin College, earned his MFA in poetry writing from Brooklyn College, and his MA and Ph. D. in English Literature from the University of Toronto. His poems have appeared in numerous journals, such as The Atlanta Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, College English, A Gathering of the Tribes, Massachusetts Review, Nimrod, Rattapallax, and Skidrow Penthouse. His Cinnamon Bay Sonnets won the Center for Book Arts chapbook competition. Earth’s Ends appeared in 2005 after winning the Pearl Poetry Award. His books of poems, Both Sides of the Niger and The Cinnamon Bay Poems, are published by Spuyten Duyvel Press and Rain Mountain Press. The travel reflected in much of his work was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He has taught at a number of colleges and universities, and currently lives in New York City. New York Quarterly Press will soon release The Rwanda Poems. |

||